The Stuff of Dreams

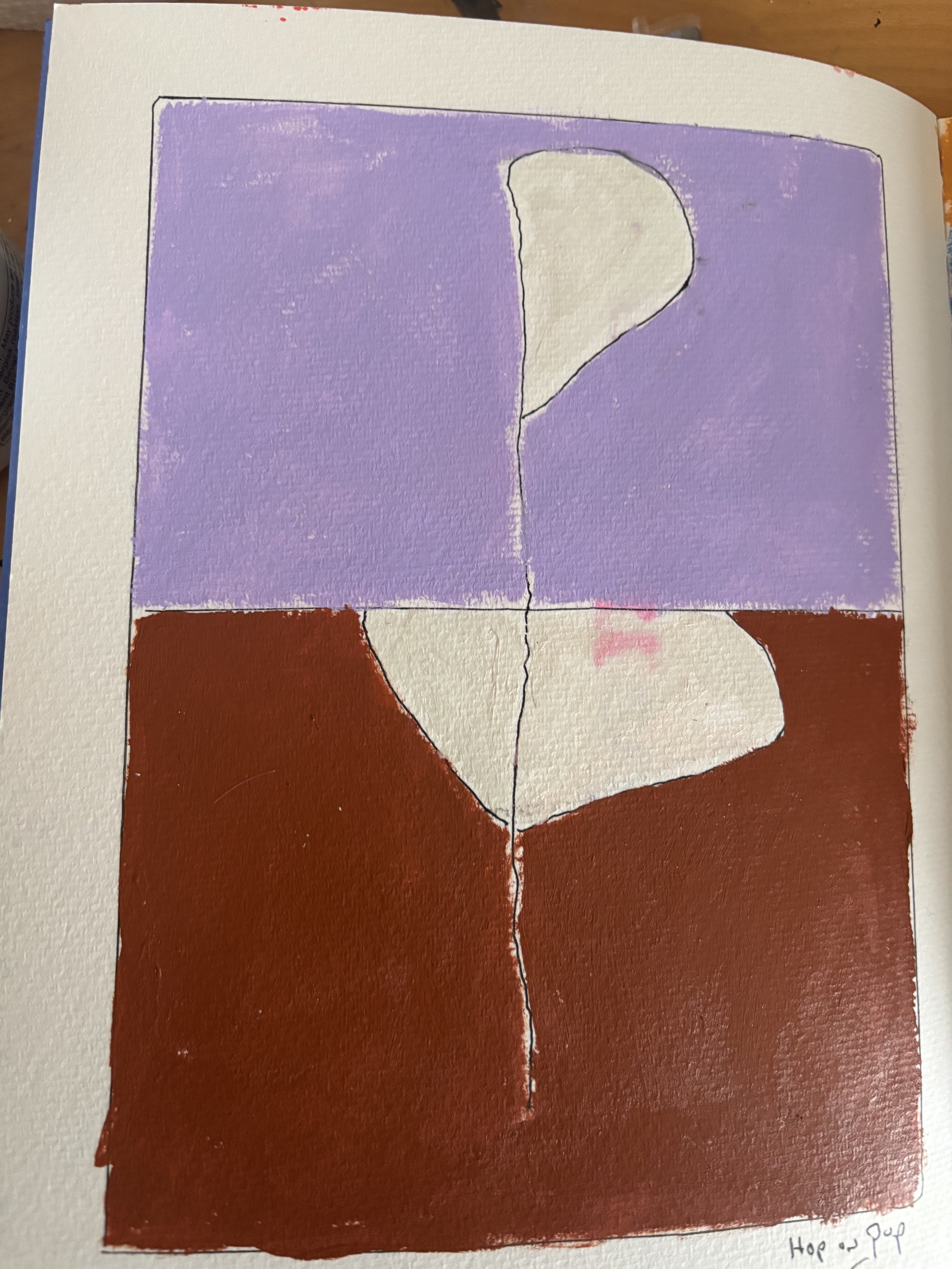

‘Hop on Pop’ sketch, acrylic on Strathmore paper, February, 2025. Photo by author.

When someone says to you, “it was just a dream you had, that’s all,” it means it wasn’t just a dream at all. Dreaming is not an end product.

Dreaming doesn’t diminish the dreamt thing, the dream often amplifies the image dreamt—the sounds, the colors, the sequence—and then seemingly disappears altogether, but not without leaving behind at least a trace of its disappearance.

Just last night I lost a dream, a dream that felt like a friend I’d just made and wanted to get to know better. By the time I woke the friend was gone.

Perhaps it wasn’t a friend at all, only a dreamt thing that had pretended to be friendly, posing in colorful clothes and smiling, singing a song you used to listen to together in high school, The Beatles or James Brown.

Losing this dream felt like I’d lost every thing: the face I was sure I’d seen, the sound of the voice and the words that were said, the brightly colored clothes—everything had vanished from the time I’d been dreaming to the time of my sudden wakefulness. Where was the dream, where had it gone, what had it looked like? I could not remember a thing, not a detail or a peep, not a ribbon or a bow, a smile or a scowl. Nothing.

It was just a dream I’d had, yet it wasn’t just a dream. It was the idea of the dream that I thought I’d had, in a sleeping mind that was only capable of dreaming, having enjoyed or been terrified by the dream, that some other consequential or meaningless event had replaced the dream I’d just lost, erasing every previous dream no matter how beautiful or terrifying. For there was no image I was seeking at the time, the dream had just come to me whether I’d asked for it or not, and I hadn’t asked.

By morning I forgotten all about the dream. It seems now that I hadn’t missed the dream at all, I’d missed the image! The image I’d been seeking was, after all, the big fat pink thumb on my right hand to which I have just affixed two thick globs of white paint.